Newswise — A college degree was far from the minds of Joshua and Caleb Marceau growing up on a small farm on the Flathead Indian Reservation in rural northwestern Montana. Their world centered on powwows, tending cattle and chicken, fishing in streams, and working the 20-acre ranch their parents own. Despite their innate love of learning and science, the idea of applying to and paying for college seemed out of reach. Then, opportunities provided through NIGMS, mentors, and scholarships led them from a local tribal college to advanced degrees in biomedical science. Today, both Joshua and Caleb are Ph.D.-level scientists working to improve public health through the study of viruses.

Joshua Discovers Unexpected Opportunities

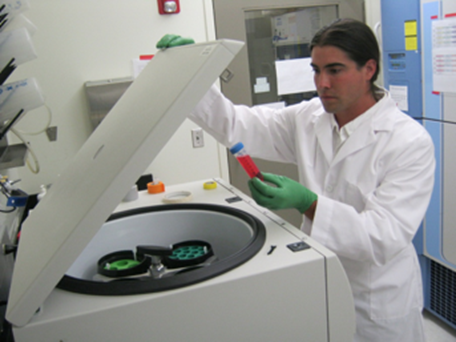

Joshua Marceau at Salish Kootenai College, where he gained research experience as an undergraduate. Credit: Joshua Marceau.

As the oldest of four brothers, Joshua was the trailblazer in the family. But like most trailblazers, his path to a scientific career wasn’t always smooth. He attended a reservation school until sixth grade, then was homeschooled. He earned his GED through the local tribal community college, Salish Kootenai College (SKC) in Pablo, so he could begin to take college-level chemistry.

When Joshua started at SKC, he was taking classes while working full time at a local waste management company hauling garbage. That changed when SKC received a Research Initiative for Scientific Enhancement (RISE) grant from NIGMS. The RISE program is designed to increase diversity in science by providing grants to institutions with a commitment to and history of developing students from populations underrepresented in biomedical sciences. The program helped SKC build a lab focused on molecular biology and biochemistry. The grant also gave support to students to work on research projects. Joshua and Caleb were the first two students at SKC to be supported as research assistants on the RISE grant.

Through the RISE program, Joshua met Mary Poss, a biology professor at the University of Montana in Missoula. Joshua and the other RISE scholars took road trips to her lab to learn basic molecular biology techniques. With guidance from SKC mentors and Poss, Joshua applied for scholarships so he could afford to quit his job and attend school full time.

Joshua followed Poss to Pennsylvania State University in University Park, where he earned his undergraduate degree in molecular biology. “I probably wouldn’t have left the reservation if I didn’t have someone to go with who I could trust,” says Joshua. “The personal mentorship needed to come first.”

He then returned home to get his Ph.D. at the University of Montana. For his dissertation, he studied vaccines for Ebola virus ![]() and hantaviruses

and hantaviruses ![]() at the nearby National Institutes of Health (NIH) Rocky Mountain Laboratory. Now, he’s conducting postdoctoral research on HIV in the lab of Julie Overbaugh

at the nearby National Institutes of Health (NIH) Rocky Mountain Laboratory. Now, he’s conducting postdoctoral research on HIV in the lab of Julie Overbaugh ![]() at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington. HIV is a major problem on the Flathead Indian Reservation where he grew up, and probably other Native American reservations

at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington. HIV is a major problem on the Flathead Indian Reservation where he grew up, and probably other Native American reservations ![]() as well, he notes.

as well, he notes.

Joshua returned to SKC this summer to give students an overview of what a career in biomedical research is like. In addition, he’s working to build bridges between the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center and SKC to give students the opportunity to experience biomedical science at top laboratories in the country.

Caleb Explores Possibilities in Biomedicine

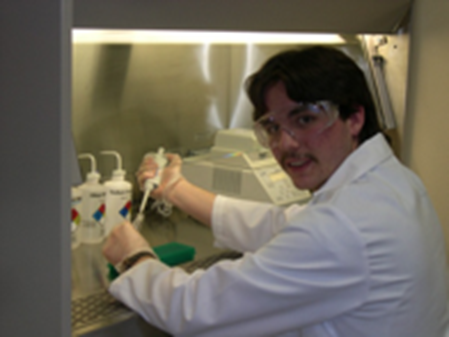

Caleb Marceau preparing specimens at SKC. Credit: Caleb Marceau.

Joshua’s younger brother Caleb, who worked changing oil and selling auto parts, was following close behind. Like Joshua, he took advantage of the opportunities provided by the RISE grant at SKC, trading his work in the garage for full-time pursuit of a college degree.

“It was very important for me to have an older brother blazing a trail,” says Caleb. “Quitting a stable job and going to college seemed like a really risky move. I don’t know if I could have done it on my own.”

Like Joshua, Caleb knew he needed a mentor to help him navigate his academic path. Through SKC instructor Michael Ceballos, Caleb met Ken Stedman at Portland State University in Oregon. Stedman invited Caleb to work in his lab and mentored him, encouraging him to finish his undergraduate degree in microbiology and molecular biology.

Caleb received an NIH undergraduate scholarship that gave him the opportunity to spend summers doing research at NIH in Bethesda, Maryland. One summer, Caleb attended a program at Stanford University for a few days. That short visit inspired him to pursue his Ph.D. After graduating from Portland State, he returned to Montana and worked for NIH at Rocky Mountain Lab before applying to graduate school. He was accepted to both Harvard and Stanford, but followed his dream to someday return to California. Caleb studied microbiology and immunology at Stanford, working on a vaccine for the dengue fever ![]() virus in the lab of Jan Carette

virus in the lab of Jan Carette ![]() .

.

After finishing his doctorate, Caleb landed a dream job working on dengue at the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub, a medical science research center funded by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan. Now, he’s a scientist at NGM Biopharmaceuticals.

Success, Thanks to Mentors, But With Bittersweet Compromises

Although the brothers encourage young students in their tribal community to pursue careers in biomedical science, they’re also frank about some of the challenges specific to Native American scientists—some of which they didn’t even imagine when they were just starting out. For example, one challenge is that there is no thriving biomedical community near the reservation. “We always expected to go home,” says Joshua, but most jobs suited for the brothers’ training are located in big metropolitan hubs.

Whatever path the Marceau brothers ultimately choose, connecting with mentors still remains a critical part of their plan. One highlight for Joshua was that he was finally able to meet Clifton Poodry, former director of the NIGMS Division of Training, Workforce Development, and Diversity who awarded SKC that first RISE grant many years ago. “I knew that Clif, a very successful biomedical scientist, was out there, but no one encouraged me to meet him,” Joshua says. “I’m so glad that I finally got to meet him, right before he retired.”

The brothers credit their mentors for helping them to not only obtain scholarships that provided necessary support, but also to navigate and succeed in an academic culture that was foreign to them and many miles away from their reservation.